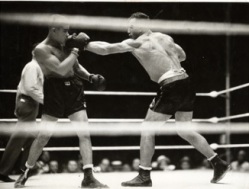

It was a beautiful right cross, straight to the jaw. The big Italian folded up in the middle of the ring. He got up and fell to his knees and got up again but he was swaying.

Yankee Stadium was full of 64,000 people tonight. A scrum of men in suits and ties and hats plus a few women who didn’t mind getting blood on their mink wraps, all roaring down from their seats at a boxing ring the size of a postage stamp. The Italian-Americans were telling Primo Carnera to stay on his feet and keep his guard up, their black hair glossy in the lights. African-Americans shouted at Joe Louis to finish him, Joe, finish him and shadow-boxed with whatever fist wasn’t holding a cigarette.

Commentators ringside talked fast into their microphones for the folks at home. Photographers popped off another bulb in cameras big as a box of groceries. Louis stalked a glassy Carnera around the ring.

Unconquered Champions

Boxing men had their money on the Brown Bomber. Carnera was a bum. A shambling man mountain from an Italian village no-one could find on the map, Carnera had been mobbed up since his first fight in America. Everyone knew Jack Sharkey took a dive two years ago. Only the gangsters who managed the Italian Giant knew how many of this former circus strongman’s other opponents got paid to hit the canvas.

The kind of men who preferred to hang around bars instead of going home to the wife had been arguing for weeks over whether this fight was rigged. The conclusion was always the same: no chance, pal. No-one alive had enough money to persuade an Italian or African-American to take a dive in the summer of 1935. Not with Ethiopia all over the front pages and war marching closer every day. Not with New York’s Italians and African-Americans at each other’s throats.

Ethiopia meant something special to Black Americans. No-one had wanted to go live there when Hubert Julian came recruiting five years ago but they loved the country as a showcase for black pride. Everyone knew that Italy had tried an invasion a few decades back and got beaten to a paste by the Ethiopians at a place called Adwa, just like Joe smearing Carnera all over the canvas tonight. Haile Selassie’s turf was a symbol of black defiance: the last unconquered nation in Africa.

That’s why there were 1,500 policemen outside the Stadium, the largest riot squad New York had ever seen. Truncheons and guns and tear gas, waiting for the trouble to start. They could hear the crowd inside roaring as the big Italian tried to shake some sense into his skull.

Carnera had guts. It was round six and he was still upright. But all 6’5’ of him was hurting. Joe Louis, fresh as rain, ducked inside the giant’s clumsy hooks and chased him to the ropes.

African-Americans in the Stadium cheered every time Louis landed a punch.

Imaginary Homeland

‘Why don’t you fight lynchings, peonage, bastardy, discrimination and segregation?’ said the front page of the Chicago Defender, one of the biggest black newspapers in America. ‘Why don’t you fight for jobs to which you are entitled? Why don’t you fight for your own independence? What advantage is there in your rescuing Ethiopia from the Italians and losing your own country to tyranny and prejudice?’

The Defender liked Ethiopia as well as anyone but there were limits. African-Americans were not long out of slavery. Down south, Jim Crow laws gave them separate water fountains and seats at the back of the bus. Up north, property prices and low wages corralled them into ghettoes. The Ku Klux Klan lynched them, the police force beat them, and justice was for white people.

The Defender liked Ethiopia as well as anyone but there were limits. African-Americans were not long out of slavery. Down south, Jim Crow laws gave them separate water fountains and seats at the back of the bus. Up north, property prices and low wages corralled them into ghettoes. The Ku Klux Klan lynched them, the police force beat them, and justice was for white people.

The past few decades had been all about pushing back. Marcus Garvey’s UNIA and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) fought the battle for civil rights an inch at a time. W.E.B. Du Bois and other intellectual types up on Sugar Hill were in the front row of a black cultural renaissance. And even the snobbiest music critic had to acknowledge that jazz was a real art form.

Then Mussolini moved his soldiers to Ethiopia’s borders and Black America forgot about its own problems. Everyone wanted to talk Haile Selassie. The boys in the Defender newsroom put up with as much as they could take then let loose on the front page. They had strong words for the community: drop this crazy talk about fighting in Ethiopia and concentrate on homegrown problems.

No-one listened. That summer Chicago was full of rallies and leaflets as Black America projected its fantasies about living free and proud onto a baked slice of inhospitable bushland. Up in New York you couldn’t walk between 125th and 145th Streets in Harlem without tripping over someone with a megaphone and a collecting bucket and an Ethiopian flag.

African-Americans followed Hubert Julian’s example and boycotted Italian shops, ice cream parlors, and icemen. Letters to newspapers poured in from correspondents calling themselves ‘Count Him In’ (Brooklyn), ‘Would Die for Abyssinia’ (Lancaster, PA), ‘How Ethiopia Must Win’ (Philadelphia), ‘Six War Vets Ready’ (Hampton, VA), and ‘Wants to Help Ethiopia’ (Cleveland). Black students in New York organised an Africa vs. the Imperialist Powers mock trial. Black churches held prayer meetings and reminded everyone that Haile’s Selassie’s empire was mentioned in the Bible. Psalms 68:31 – ‘Princes shall come out of Egypt; Ethiopia shall soon stretch forth her hands unto God’.

The UNIA got in on the action. Back in the glory days of the 1920s Marcus Garvey’s men had marched through Harlem in uniform, a biplane flown by Julian swooping overhead. Garvey’s deportation to Jamaica put the UNIA into a long-term coma but it woke up when his successor in New York, Captain Alfred L. King, started protesting Haile Selassie being pushed around by Italy.

Captain King had plenty of competition. The Pan-African Reconstruction Association (PARA) talked about sending volunteers to fight, the African Patriotic League made a lot of noise, and the Provisional Committee for the Defense of Ethiopia (PCDE) got the biggest numbers by bringing together Elks lodges and other national organisations.

Haile Selassie’s supporters had enthusiasm but not much practical knowledge about Ethiopia. The country was a big, blank, symbolic spot on the map. In the 1920s the Tutt Brothers, toast of black vaudeville, ran a show that claimed jazz came from Ethiopia. No-one argued the point. Hubert Julian knew the country first hand but he was out in Addis Ababa mixed up in all kinds of intrigue. In his absence the organization found itself suggesting everyone read articles from pulp rag Adventure and follow them up with L. M. Nesbitt’s Hell Hole of Creation, a book not much subtler than its title.

This lack of information meant Ethiopia’s friends welcomed any well-informed white folks who wanted to help out. No-one cared if the new arrivals were red as Moscow. Groups like the PCDE were happy to work with the Communist Party and pretended not to notice when the comrades mixed some Marxist thought with their support for a black emperor. A united front seemed more important than redbaiting and white hating.

Only journalist George Schuyler, a hero to the thin slice of African-Americans who leaned so far right they were practically horizontal, took a contrarian view and told the world what he thought of the community’s new white friends.

‘Professional Negrophile busybodies and self-appointed shepherds of the Negro races,’ he said, ‘who believe nothing can be done by or for Negroes unless a white man is directing it.’

Most of the action, left-wing or not, took place up north. Down south things were quieter because no-one wanted the Klan turning up at midnight. But all parts of the country were listening to the radio when Joe Louis went up against Primo Carnera at Yankee Stadium.

Fighting Back

Carnera went down again with another right cross to the jaw. He was on one knee in the ring and the referee was pushing Louis back. Then the Italian giant was upright with the dull panic of a man taking a beating he can’t stop.

Anyone would panic with the Brown Bomber coming at them. Joe Louis was a tasty young heavyweight with a sulky look on his face and a talent for killer knock-outs. The son of dirt-poor Alabama sharecroppers, with a dash of Cherokee on his mother’s side, Louis took up boxing to stay out of trouble when the family moved to Detroit. Yankee Stadium was another stop on the road to the heavyweight championship. Carnera was just another obstacle.

The referee checked the Italian’s eyes and got out of the way. Louis went in swinging. Howls of support from the Brown Bomber’s fans rolled around the Stadium. This was the kind of direct approach to Fascism they could get behind.

The referee checked the Italian’s eyes and got out of the way. Louis went in swinging. Howls of support from the Brown Bomber’s fans rolled around the Stadium. This was the kind of direct approach to Fascism they could get behind.

Thousands of black men had already signed up to fight for Ethiopia, drawn by idealism, racial solidarity, and the promise of a steady job. Samuel Daniels of New York’s PARA and Harold H Williams of the Ethiopian League of America travelled cross country signing up volunteers. By the time Louis stepped into the ring they had 1,000 in New York; 1,500 in Philadelphia; 8,000 in Chicago; 5,000 in Detroit; and 2,000 in Kansas City. Daniels had no problems getting rich off a good cause: he charged 25 cents per enlistment, with higher rates for officers.

A group calling itself the Black Legion, under Sufi Abdul Hamid aka Eugene Brown (a Muslim convert known as the ‘Black Hitler’ for his anti-Semitic speeches), claimed to have 3,000 volunteers at a training camp in upstate New York. Another group talked about chartering a freighter to take 2,000 volunteers to Africa. Journalists and police were never allowed to get close enough to see if anyone was telling the truth.

Ethiopia wasn’t much interested in foreign volunteers, but a courtier’s diplomatic reply when black newspaper The Pittsburgh Courier sent Haile Selassie a telegram on the subject was misinterpreted as something more positive. The resulting story inspired thousands to contact Melaku Emmanuel Bayen, Ethiopian doctor and man behind the Pan-Africanist Voice of Ethiopia newspaper. They figured he had some pull as Haile Selassie’s cousin. They’d even forgiven him for recruiting Hubert Julian back in 1930.

Bayen knew his relative well enough to turn down volunteers. He advised everyone to follow his example and work peaceably with a white-run group like the Ethiopia Research Council. Privately, Bayen disagreed with cousin Selassie’s stand on foreigners and had already sent a black pilot called John Robinson down the pipeline to Addis Ababa.

The dogs of war did not give up easily. Would-be mercenaries contacted the Ethiopian consul in New York, a sad-faced and big-nosed businessman called John H. Shaw. It was another dead end. Addis Ababa had already instructed the white forty-eight-year-old to turn away anyone who wanted a visa. Shaw did as he was told and got thanked by having to pay the rent on his own consulate when the Ethiopians forgot about him.

Washington put the final shovel of soil on the coffin by announcing new penalties for anyone enlisting in a foreign army against a nation not at war with America. The mix of African-American uproar and leftist agitation triggered the politicians into handing down three years in prison and a $2,000 fine. Haile Selassie’s most fanatical defenders claimed they would still find a way. The government told the FBI to keep an eye on them and refused to issue passports to anyone heading for East Africa.

Only white Americans (then about 88% of the population) could support Haile Selassie without the government getting too concerned. Most thought Italy should stay out of Ethiopia, a surprise to opinion pollsters who knew how popular Mussolini had been until recently. A lot of folks saw Fascism as a supercharged patriotic capitalism, dynamic but unthreatening. They covered their ears when Il Duce’s speeches threatened to burst the peace bubble.

‘War is to man as maternity is to women,’ said Mussolini. ‘I do not believe in perpetual peace; not only do I not believe in it but I find it depressing and a negation of all the fundamental virtues of man.’

White America finally realized the man in Rome was serious when Blackshirt soldiers began sailing for Africa. By the summer of 1935 enthusiasm for Mussolini had dropped away. Soon only Italian-Americans were left to cheer on Il Duce and his dreams of a reborn Roman Empire.

Out in the lonely centre of Yankee Stadium, Primo Carnera was a shambling mess. The Italian’s hands were drooping and Louis was taking him apart.

Hotsy-Totsy

Carnera’s face took a hard right cross that sprayed sweat over the ringside seats. The Italian went down for the third time. The referee pushed Louis back. Carnera made it to his feet but the big guy was wobbling all over the ring with no more fight left in him. The referee waved his arms and ended the punishment. Technical Knock Out.

It was Louis’ twentieth win out of twenty matches, and his seventeenth knock out. The ring filled with the fighters’ people; the crowd’s shouts rolled across the stadium like a thunder storm.

It was Louis’ twentieth win out of twenty matches, and his seventeenth knock out. The ring filled with the fighters’ people; the crowd’s shouts rolled across the stadium like a thunder storm.

Police checked their riot gear and got ready to crack some skulls as Yankee Stadium drained into the streets. But to everyone’s surprise there was no trouble that night. African-Americans were too happy and Italians too depressed to throw punches. The lights went out in the spaghetti district while Black Harlem lit up in an ocean of white enamel and cheering and climbing lamp posts to pose for the cameras.

‘Everything is hotsy-totsy and the goose is hanging high,’ said a correspondent for the Pittsburgh Courier.

Things weren’t so hotsy-totsy over in Addis Ababa. The Italians were on the border and Haile Selassie had begun to realise the League of Nations weren’t going to intervene. The only foreigners around were newsmen hunting down stories, and adventurers looking for action. One of them, a mercenary pilot called Hugh de Wet, was heading in right now from Djibouti, a coastal town nobody loved.

And he needed a drink.

Find out more about foreign involvement in the Italo-Ethiopian War with my book:

Lions of Judah: Haile Selassie’s Mongrel Foreign Legion [or amazon.com]

Or show some love for this blog by buying my books in paperback, hardback, or ebook. It all helps.

The Men from Miami: American Rebels on Both Sides of Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution [or amazon.com]

![]() The King of Nazi Paris: Henri Lafont and the Gangsters of the French Gestapo [or amazon.com]

The King of Nazi Paris: Henri Lafont and the Gangsters of the French Gestapo [or amazon.com]

![]() Soldiers of a Different God: How the Counter-Jihad Created Mayhem, Murder, and the Trump Presidency [or amazon.com]

Soldiers of a Different God: How the Counter-Jihad Created Mayhem, Murder, and the Trump Presidency [or amazon.com]

![]() Lost Lions of Judah: Haile Selassie’s Mongrel Foreign Legion 1935-41 [or amazon.com]

Lost Lions of Judah: Haile Selassie’s Mongrel Foreign Legion 1935-41 [or amazon.com]

![]() Katanga 1960-63: Mercenaries, Spies and the African Nation that Waged War on the World [or amazon.com]

Katanga 1960-63: Mercenaries, Spies and the African Nation that Waged War on the World [or amazon.com]

![]() Franco’s International Brigades: Adventurers, Fascists, and Christian Crusaders in the Spanish Civil War [or amazon.com]

Franco’s International Brigades: Adventurers, Fascists, and Christian Crusaders in the Spanish Civil War [or amazon.com]

One reply on “Blood on the Canvas: African-Americans, Haile Selassie, and Italian Fascism”

[…] Blood on the Canvas: African-Americans, Haile Selassie, and Italian Fascism […]

LikeLike