Wednesday, 22 August 1962. Ten past eight in the evening.

It was just a yellow Estafette van parked in front of a hedge on the road to Villacoublay. The few pedestrians around didn’t pay it any attention.

If they had, they would have seen Serge Bernier sitting in the very back, a slim and blond Korean War veteran with startlingly blue eyes. A man called Lazlo Varga at the wheel. Three men in the back seat: Gérard Buisines, and the Hungarians known as Sari and Marton.

Observers might have wondered why Bernier was scanning the road with a pair of binoculars. The answer was simple: Charles De Gaulle’s limousine sometimes used this route. And the men in the van were trying to kill him.

In the Line of Fire

Bernier was peering through the evening murk at a bus stop down the road. A tall military-looking man with dark hair and eyebrows like caterpillars was standing there, ostentatiously opening and closing his newspaper. De Gaulle’s limousine, accompanied by a car full of security men and two motorcycle outriders, had just passed.

It was too dark. Bernier could not see the signal.

What the Frenchman suddenly could see was De Gaulle’s limousine hurtling out of the evening murk only sixty yards away. He kicked open the Estafette’s back door and opened fire with his submachine gun.

“Come on!” he shouted.

Sari and Marton boiled out of the side door and knelt by the front wheel, firing their submachine guns. De Gaulle’s car shot past them taking no evasive action, followed by the security detail. Bernier joined them at the front wheel to shoot at the limousine as it sped away.

A passerby, lost in his own thoughts, strolled in front of Bernier’s gun barrel.

“Hey you!” Bernier shouted. “You’re in my line of fire.”

“I’m so sorry,” said the man, backtracked, and passed the van on the hedge side. He was still deep in thought.

The limousine swerved: the right front tyre had blown. It barely missed an oncoming car. Then the convoy was out of sight. The shooting had lasted only a few seconds.

Further up the road an Idée, stolen earlier that day and stuffed full of Frenchmen with submachine guns, was lumbering out of a side turning to block De Gaulle’s escape. Like the men in the Estafette, they were members of the OAS, Europe’s largest and deadliest right-wing terror group.

They were determined to kill Charles De Gaulle.

Algérie Française

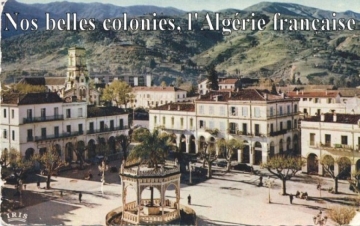

The President of France was about to die because of a parched slab of land lying along the North African coast. Most of Algeria was desert and the rest only a few buckets of water away from joining it. But men and women had loved this land intensely over the centuries. Phoenicians, Romans, and Ottoman bricked it into their empires. In 1830 France took its turn.

Algeria was only 454 nautical miles from Marseilles across the sparkling blue of the Mediterranean. The men from Paris improved irrigation and built farms across the hard soil. The capital Algiers expanded into a mess of narrow streeted souks and white-washed villas. Oran breathed in fresh breezes off the ocean.

Native Algerians did not get to enjoy their own country much. They were nudged aside by white immigrants, a salad of French, Italians, and Spanish known as Pied Noirs. The Algerians thought bitterly that it was a beautiful country – if you were white. Your morning dose of cafe au lait et un Gauloise unfiltered outside a cafe in Algiers with the North African sun warming your face. A steady job at shipping business where the career ladder was held steady for you. A spacious apartment in Oran with the Mediterranean Sea flat and blue through the windows, Algerian servants, respectful and underpaid. Figs and wine and tanned brown limbs.

Not all whites lived like this. Many were desperately poor, scraping a living as dockworkers and garage mechanics. But to native Algerians, Arab or Berber, being white was to live on a sundrenched honeycomb.

La balance held until the end of the Second World War. Then decolonisation and Soviet propaganda and middle-class doubt about the imperial dream combusted with Algerian nationalism and a few drops of Islam.

In 1954 French soldiers in remote outposts were ambushed and slaughtered. Families driving to check on farming relatives out in the steppes found them dead on the kitchen floor with their throats cut. The Front de Libération Nationale (National Liberation Front – FLN) was responsible.

Hard-eyed French paratroops went out for revenge and to prove they could do more than surrender to Germans. They adopted the tactics of counter-revolution. Political reform (mild), relocation of populations (forced), torture (unbearable). The FLN got beaten out of the countryside and holed up in the city. It seemed like victory but then bombs started going off in Algiers’ white-frequented cafes. Now it was urban warfare.

Hard-eyed French paratroops went out for revenge and to prove they could do more than surrender to Germans. They adopted the tactics of counter-revolution. Political reform (mild), relocation of populations (forced), torture (unbearable). The FLN got beaten out of the countryside and holed up in the city. It seemed like victory but then bombs started going off in Algiers’ white-frequented cafes. Now it was urban warfare.

The army went to war in the cities. Bombs kept exploding and it was the ordinary people walking the streets who got killed. Soon Pied Noir civilians began fighting their own parallel war against the FLN. Some had seen family and friends from the block get killed by Algerians they lived side by side with. Others believed in the greatness of the French empire. Others just hated Arabs. Gangs of men got together and dug up old hunting rifles and submachine guns held onto after military service.

“On a side street in the centre of Algiers there was an Arab who sold eggs for a living. Every day you would see him there with his tray of eggs. One day he was blown to smithereens. When I ran into [Jean-Jaques] Susini that evening, he exclaimed, ‘Well, are we going to [use tactics like the FLN], yes or no? The eggseller was the first to go. Now they’ll understand’.”

The FLN kept fighting. France’s military muscle was strong but the political will weak. The army watched suspiciously for any signs of a stab in the back. In 1958 they thought they saw it in René Coty’s government. No-one called what happened next a coup. General Charles De Gaulle, France’s Second World War hero, became president on a promise of “Algérie française” toujours.

He lied. The year after taking power De Gaulle realised the war against the FLN was unwinnable. He announced measures that would lead inevitably to independence.

The army tried the coup trick again in 1961. This time it failed. De Gaulle was now even more determined to cut Algeria loose. But he had a new enemy. In the coup aftermath hundreds of right-wing soldiers deserted the army. They turned up weeks later with fake IDs and new friends in Algiers apartments and Oran villas, determined to stop Algerian independence.

The highest ranking defector was General Raoul Salan. He went into exile in Francoist Madrid and announced his war to keep Algeria French. His leadership brought together existing Pied Noir gangs and French nationalists over the water. The deserting soldiers formed connective tissue to bind everyone together into a powerful paramilitary underground army. They would do anything and kill anyone – even De Gaulle – to keep Algeria French.

The Organisation de L’armée Secrete (Secret Army Organisation). The OAS.

Twilight for France

“Salan and his lieutenants believe that what is being tested in Algeria is not the right of peoples to self-determination, but the will of the West -or at least France – to defend itself against its mortal enemies,” said an article in America’s Harvard Crimson magazine. “The O.A.S. unabashedly calls the Algerian fellaghas the enemies of the West, just as the Communists are. There is a strong racist strain in their position, of which they are not ashamed.”

The Harvard Crimson was on the right track but the OAS was a broader church than its critics liked to believe. Members included Algerians who preferred Paris to the FLN; Jewish Pied Noirs in Oran who did not want to see a Muslim state in their lifetimes; members of the communist party who dodged the party line on colonialism; Georges Bidault, former French Prime Minister; even Jean Kay who would hijack an Air Pakistan jet in 1971 to demand food for the starving in Bangladesh.

But the majority were men of the right. And it was men. Women supported the Pied Noir struggle, providing safe houses and banging pots and pans every night out their windows to the beat of “Alg-ér-ie fran-çaise; Alg-ér-ie fran-çaise”. Some acted as spies and informers. But in the macho world of French Algeria they were always the woman behind the man behind the gun.

The core of the OAS was men like Army deserter Roger Degueldre, leader of the assassins in the Delta Commando; Jean-Jacques Susini, killer of eggsellers and far-right political brain of OAS; men who thought Vichy was the best government France ever had; men who thought Arabs only existed to make life easier for the whites.

The right loved the OAS. Neo-fascist young men of Jeune Nation paraded through the streets of Algiers with metal celtic crosses on long poles, like far-right priests. The celtic cross turned up in OAS graffiti. It also turned up at the scene of France’s biggest bank robbery in Nice, 1976 long after the OAS had disbanded.

The organisation had hardcore local support. It killed Arabs with impunity and fought the FLN bullet for bullet and bomb for bomb. When the French authorities turned on them, OAS killers loaded an intercepted printing press with plastic explosive and sent it to a villa stuffed with De Gaulle’s spies.

Salan’s men even tried to kill De Gaulle. They were not alone. Partisans of French Algeria tried to assassinate the head of state thirty-one times. Some attempts were amateur – like the drunken playboy who tried to crash his private plane into De Gaulle’s helicopter but got confused by the swarm of choppers that took off with him. At Petit-Clamart the OAS were better prepared.

L’Organisation de L’armée Secrete was the largest and best-organised right-wing terror group Europe had seen. It had the support, through enthusiasm or fear, of most whites in Algeria and many on the mainland. Sympathetic policemen and army officers; shop owners and postmen. George Bidault cared enough about Algérie française to abandon his respectable life and go underground.

The men of the OAS fought against decolonialisation, against democracy, against their own government. They never spent more than a few years in prison. Later they would be entwined with the birth of the Front National, the far-right party now challenging the French political establishment. Skinny, balding Jean-Jacques Susini was condemned to death twice by De Gaulle’s government. But he went on became a Front National senator.

Algeria got its independence in 1962. The OAS had nothing left to fight for except revenge. De Gaulle would pay for betraying them. Susini organised the attack on the road to Villacoubloy.

I Think You Got Him

Georges Watin had a head shaped like an upside-down bucket and a body like a gorilla. He was fat and he limped.

Watin was only half in the passenger seat of the Idée when La Tocnaye screeched the car into the road, expecting to see De Gaulle’s convoy in pieces to their left, ready to be finished off. Instead the convoy shot past them along the avenue De la Liberation. La Tocnaye, an undersized aristocrat with an outsized pride in his family tree, accelerated after them, overtaking the car containing the bodyguards.

Watin’s leg was dr agging on the ground out the open door as he opened fire with his Sterling submachine gun.

agging on the ground out the open door as he opened fire with his Sterling submachine gun.

La Tocnaye could see figures moving in the back of de Gaulle’s limousine.

“I can see them!” he shouted.

A burst from Watin’s submachine gun smashed the limousine’s back window.

“Georges, you’re dead on!”

Watin’s gun jammed. As he tried to clear the breech, the car with de Gaulle’s bodyguards cut in front of them. Behind, two motorcycle outriders were gaining fast, trying to draw their guns. La Tocnaye was passing his gun to someone in the backseat when Watin fixed the Sterling and sprayed the motorcyclists’ tyres. They spun off the road and disappeared in the dark.

La Tocnaye saw a roadblock ahead in the distance. He screeched the van into the next road on the right and headed for the motorway.

“I think you got him, Georges,” he said.

At a small flat in Passy, a pretty Pied Noire called Ghislaine kissed La Tocnaye and Watin on the cheek and told them they had failed.

De Gaulle was still alive.

Here’s a not entirely accurate recreation of the assassination attempt from 1973’s Day of the Jackal.

For English language background on the OAS, the best is 1989’s Challenging De Gaulle by Alexander Harrison but 1970’s Wolves in the City by Paul Henissart has its good points. General history on the Algerian conflict can be found in Alistair Horne’s A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962 (1977). Objectif De Gaulle by Christian Plume and Pierre Demaret, the history of OAS assassination attempts on President De Gaulle, is available as the entertaining English language Target: De Gaulle (1976), complete with rip-off ‘Day of the Jackal’ cover.

If you want to show some love for this blog then buy my books in paperback, hardback, or ebook. It all helps.

The Men from Miami: American Rebels on Both Sides of Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution [or amazon.com]

![]() The King of Nazi Paris: Henri Lafont and the Gangsters of the French Gestapo [or amazon.com]

The King of Nazi Paris: Henri Lafont and the Gangsters of the French Gestapo [or amazon.com]

![]() Soldiers of a Different God: How the Counter-Jihad Created Mayhem, Murder, and the Trump Presidency [or amazon.com]

Soldiers of a Different God: How the Counter-Jihad Created Mayhem, Murder, and the Trump Presidency [or amazon.com]

![]() Lost Lions of Judah: Haile Selassie’s Mongrel Foreign Legion 1935-41 [or amazon.com]

Lost Lions of Judah: Haile Selassie’s Mongrel Foreign Legion 1935-41 [or amazon.com]

![]() Katanga 1960-63: Mercenaries, Spies and the African Nation that Waged War on the World [or amazon.com]

Katanga 1960-63: Mercenaries, Spies and the African Nation that Waged War on the World [or amazon.com]

![]() Franco’s International Brigades: Adventurers, Fascists, and Christian Crusaders in the Spanish Civil War [or amazon.com]

Franco’s International Brigades: Adventurers, Fascists, and Christian Crusaders in the Spanish Civil War [or amazon.com]

3 replies on “The Plot To Kill Charles de Gaulle”

[…] The Plot To Kill Charles de Gaulle […]

LikeLike

[…] the Mouvement D’Action Civique, a nationalist group into karate and cheerleading for French extreme rightists. By 1963 it had morphed into Jeune Europe and claimed branches in Italy, France, Portugal, and […]

LikeLike

[…] worse, Lagaillarde was opposed to assassination attempts on De Gaulle, thinking them counter-productive. He told to Spaggiari to wait until he got a direct order before […]

LikeLike